DAEI investigations in autumn 2017

By Tim Skuldbøl and Carlo Colantoni

Acknowledgements

On 25 October 2017 DAEI signed a new 5-year contract with the Directorate General of Antiquities and Heritage to investigate the archaeological sites of Babukur, Basmuzian and Girdi Gulak. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Abu Bakir Othman Zenniddin (Mala Awat), Director of the Directorate General of Antiquities and Heritage and his staff for this opportunity, as well as their kind support and assistance for the DAEI project.

We are also grateful to Barzan Baiz Ismail - Director of the Raparin Antiquities Directorate and the Raparin Civilization Museum - his staff and our local employees and guards from the towns of Rania, Chwarqurna and Boskin.

The 2017 season was kindly sponsored by the Danish Institute in Damascus and the Beckett Foundation.

Aims of Investigations

The 2017 fieldwork season, which represents the beginning of Phase 2 of DAEIs investigations took place between 29th September and 4th November 2017. The aims of the season were to explore the Late Chalcolithic period (LC) deposits at the site of Girdi Gulak.

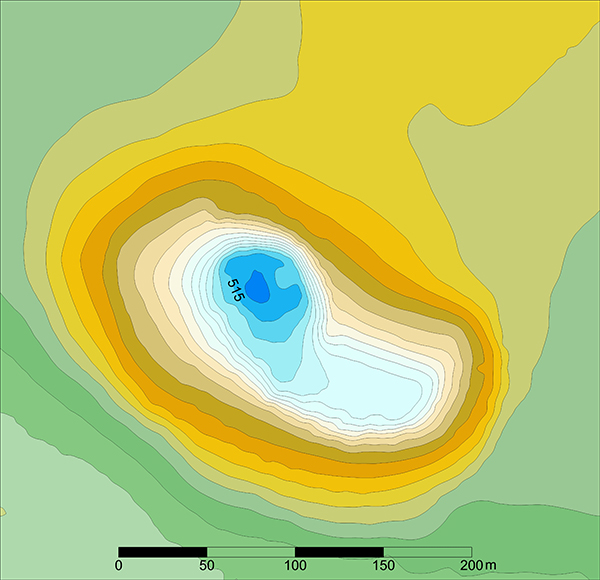

Girdi Gulak lies about 5 km south of the modern city of Rania and about 3 km north of the site Babukur. It is an elongated mound about 4-5 ha in size, and rises about 15 m above the plain. Surrounded by numerous small ridges and natural springs the site is situated in a favourable environment for human occupation. DAEI’s investigations (surface survey and soundings) in autumn 2016 of Gulak and the surrounding area provided evidence of substantial LC (see DAEI 2016 report), as well as Neo-Assyrian and later periods, occupation at the site. Previous work by the Iraqi Antiquities Department at Gulak, or Kullak as it was called in the 1950s, suggests that occupation at the site dates to the prehistoric, Assyrian, Median and Islamic periods.

The 2017 DAEI team was smaller than usual due to the closure of International Airports from the end of September by the Iraqi authorities in Baghdad. The team consisted of Tim Skuldbøl (Director), Henrik Brahe (Photographer and Archaeologist), Martin Makinson (Archaeologist) and Sanne Lindequist (Archaeological Assistant) with online support by co-directors Carlo Colantoni and Mette Marie Hald.

The team was kindly assisted by Barzan Baiz Ismael (Representative and Director of the Raparin Antiquities Directorate of Antiquities), and Deljat Abdullah (Archaeologist, Raparin region); as well as local staff, drivers and guards: Abdullah Rahman, Abu Hassan, Ahmed Ali, Bahzad Hassan, Baiz Ismael, Djutiar Khaled, Juan Rasul, Khaled Baiz, Khedr Hassan, Mohammad Baiz, Nigar Ibrahim Khdr, Rekan Djengi, Sabast Ahmed, Sarkar Mohammad, and Sherzad Hassan.

Archaeological Investigations

DAEI’s autumn 2017 investigations comprised of:

- Site damage assessment and topographical survey at Girdi Gulak.

- Excavation and soundings at Girdi Gulak.

- The study of ceramic evidence and the processing of archaeological samples.

- Opening of the Danish Expedition Gallery at the Raparin Civilization Museum

A. Site damage assessment and topographical survey at Girdi Gulak

A significant element of DAEIs investigations at Girdi Gulak is the assessment and monitoring of the damage of the site by recent human activities. Destructive farming activities, such as ploughing and terracing or flattening by bulldozer as well as modern construction work are major threats to sites on the Rania Plain. Each year Girdi Gulak and the surrounding archaeological landscape are being ploughed and illegal bulldozing activities are visible in many locations at the site.

Flooding by Lake Dokan is another major threat to Girdi Gulak. The construction of the Dokan Dam in the late 1950s resulted in the site and its surroundings being frequently partially flooded or even submerged. In 2016 and 2017 the slopes of Girdi Gulak and the surrounding undulating landscape were flooded by the lake. Building upon DAEI’s 2016 surface survey of Girdi Gulak and its surroundings, in 2017 DAEI inspected and recorded recent damage to the site with a UAV / remote control drone, taking photographs and producing a topographical map of the site (Figure 5).

B. Excavation and soundings at Girdi Gulak

In 2017 DAEI resumed its program of targeted soundings and corings at Girdi Gulak. The project focused on the central parts of the mound where abundant LC and Iron Age surface finds were collected in 2016. The undertaking provided valuable insights into the nature and sequence of occupation at Gulak, and allowed us to begin the reconstruction of the historical biography of the site.

During the season 2017 DAEI excavated six new 2x2m soundings and continued investigations in Sounding 16 (Figure 6). Three of these soundings (S16, S21 and S23) were extended to explore and define archaeological deposits. This work resulted in the recovery of extensive remains from the Late Chalcolithic, as well as Iron Age periods. In the majority of soundings deposits from the final periods of occupation at the site were recovered; these included numerous recent Islamic graves.

Late Chalcolithic occupation at Girdi Gulak

DAEI’s investigations at Gulak in 2017 produced significant deposits dating to the Late Chalcolithic period (LC). Sherds and finds from the LC period were recovered from all of the 2017 soundings. In situ LC occupational deposits, however, were only excavated in Soundings 20-23.

The most significant remains came from Sounding 21 that produced LC deposits dating to the LC1-4 periods. Regrettably, the upper LC deposits were damaged by modern ploughing and numerous recent Islamic graves - possibly related to 20th century habitation at Girdi Gulak. From lower levels DAEI recovered remains of a large or multiple buildings dating to the early LC period (Figure 7).

These lower deposits contained diverse assemblages of ceramic dating to the LC1-2 period (Figure 8). Preliminary studies identified North Mesopotamian types, including painted chaff tempered wares as well as incised and combed wares known from the Erbil Plain. The assemblage also consisted of ceramic types known from Northwest Iran, such as Dalma/Pisdeli wares, which suggest cross-regional interaction at play.

Later LC deposits representing trash dumping and firing activities were found within and above the abandoned buildings. Ceramics included classic LC3 chaff tempered wares, as well as southern Mesopotamian types which are widely distributed on the Rania Plain (Figure 9).

Sounding 22 produced LC trash deposits which were possibly associated with the buildings and activities in Sounding 21. The finds from Sounding 22 include pottery production tools such as a ring scraper and a collection of curious clay lumps possibly used for supporting pots (Figure 10). Additional LC deposits were recovered from Sounding 20. These deposits were possibly related to outdoor activities.

Iron Age occupation at Girdi Gulak

Remains of the Iron Age period is also well attested at Gulak. Iron Age occupational deposits from the Neo-Assyrian period were uncovered in most of the 2017 soundings.

These results confirm DAEI’s 2016 surface survey, which identified Iron Age remains across the site. Important Neo-Assyrian remains were found in Sounding 16 and Sounding 23.

In 2016, excavation of Sounding 16 located at the northern base of Gulak uncovered parts of a large wall. The date of this wall, however, was ambiguous due to the mixed dates (Late Chalcolithic and Iron Age) of the deposits found above the wall. As a result, the project reopened and extended Sounding 16 to define and detail the date of its construction and use. This work resulted in the identification of a large fortification wall made of mudbrick and a water well lined with baked bricks (Figure 11-12). Current evidence implies that the well cut into the large wall. Finds from within the well, as well as from beneath the wall, suggest that both wall and well date to the Neo-Assyrian period.

From Sounding 23, located in the centre of Gulak, the DAEI project discovered further evidence Neo-Assyrian period occupation. Below indistinct Iron Age deposits, we uncovered a large mud brick building dating to the Neo-Assyrian period. The monumentality of the walls, in conjunction with the finds associated with the building, suggest that it might have be a public building (Figure 13).

C. The study of ceramic evidence and the processing of archaeological samples

In 2017 DAEI continued the analysis and processing of pottery excavated from previous seasons. On-site work resulted in an additional collection of flotation and soil samples which will undergo extensive scientific laboratory analysis. The samples (botanical, soil, animal bone, macro-finds and lithic) from 2017 were processed and have been prepared for export in 2018.

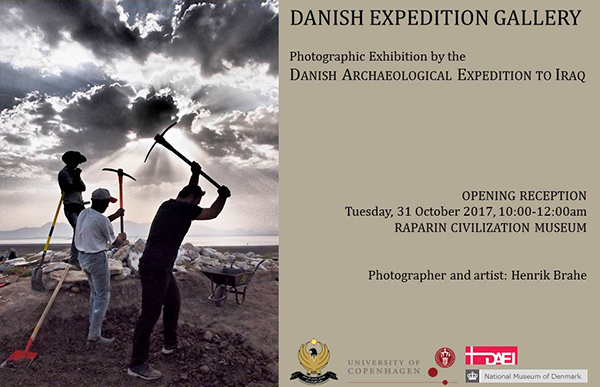

D. Opening of the Danish Expedition Gallery at the Raparin Civilization Museum

DAEI, in collaboration with the Raparin Antiquities Directorate, had the pleasure of recently curating the ‘DANISH EXPEDITION GALLERY’; the first - and permanent- exhibition at the Raparin Civilization Museum in the city of Rania. The official opening took place on Tuesday 31th October 2017. In attendance was the Governor of the Raparin Province, many local luminaries and a large press corps, including television, radio and print journalists (Figures 14-15).

The new gallery hosts a photographic exhibition featuring the work of photographer and artist Henrik Brahe documenting the first 5 years of the Expedition’s archaeological work on the Rania Plain. Henrik Brahe is a celebrated Danish artist who has had many international exhibitions. With this wonderful exhibition, DAEI aims to inform and engage the people of the Raparin Governorate with the work of the project and Iraqi heritage. The exhibition is a great way of experiencing the rich archaeological past of the region and will be accessible to members of the general public, school and university students for many years to come.

Future Plans of the Danish Archaeological Expedition to Iraq

With the signing of a new research contract in October 2017 DAEI will embark on a new 5-year phase of research. Future research will continue to investigate the sites of Babukur, Basmusian and Girdi Gulak and their immediate surroundings for evidence of patterns of early urban organization and sprawl.

DAEI will further investigate and validate new approaches and understanding of the emergence of early urbanism in Northern Mesopotamia; an understanding that challenges many presently held assumptions and is making a valuable contribution to urban studies.

Further reading

For weekly updates of fieldwork and photographs of the DAEI project: www.facebook.com/babwkur

For comprehensive reports on the DAEI project and its fieldwork: www.urbarch.tors.ku.dk