DAEI investigations in autumn 2016

By Tim Skuldbøl and Carlo Colantoni

Gulak on the Rania Plain (UAV image: Henrik Brahe, autumn 2015)

Aims of Investigations

The 2016 fieldwork season took place between 28th and 31st October 2016. The research aims of the season were to finalise DAEI’s survey in the region of Chwarqurna, and to explore the site of Gulak and its surroundings with a systematic strategy of sampling and collection of surface material, coring and soundings.

In 2016 DAEI’s team consisted of Tim Skuldbøl (archaeologist, Director), Carlo Colantoni (Survey leader and co-Director), Henrik Brahe (Photographer, artist and UAV/drone specialist), Martin Makinson (Archaeologist) and Kirstine Krath Nielsen (archaeobotanist).

The team was kindly assisted by Barzan Baiz (Director of the Raparin Directorate of Antiquities) and Kamal Rasheed Raheem (Director of the Sulaimaniyah Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage).

Figure 1. The site of Ibrahim Kathal in Lake Dokan The project assists in monitoring and protecting the archaeological heritage of Rania Plain. This involves visiting, investigating, assessing and recording sites under threat (Photo: Henrik Brahe, autumn 2016).

Archaeological Investigations

DAEI’s autumn 2016 investigations comprised of:

- A. Survey of sites on the Rania Plain in the region around Chwarqurna.

- B. Investigations of the site of Gulak and its surroundings.

- C. The study of ceramic evidence and the processing of archaeological samples.

A. Survey of sites on the Rania Plain in the region of Chwarqurna

In the autumn of 2016 the project completed the last sections of the DAEI’s contribution to the Rania Plain Survey (RPS); initiated in 2013 (Figure 1). Work in the autumn led to the identification and collection of 18 new sites (including satellite mounds), adding to our understanding of the unusually dense and complex occupation of the Rania Plain (Figures 2 and 3). This brings the total of sites and landscape entities recorded by the DAEI project to 73. New cases of urban settlement sprawl from the Late Chalcolithic period were identified around two major sites of this period on the plain: Gulak and NN (possible name Girdirash). A schedule of systematic investigations of the two sites was completed. This consisted of extensive surface collections, mapping and detailed recording (photographs, features, etc.).

Figure 2. Survey at NN (possible name Girdirash) (Photo: Henrik Brahe, autumn 2016)

Figure 3. The 2016 survey area with the newly identified sites no. 56-73 (WorldView-2 satellite image, 2010)

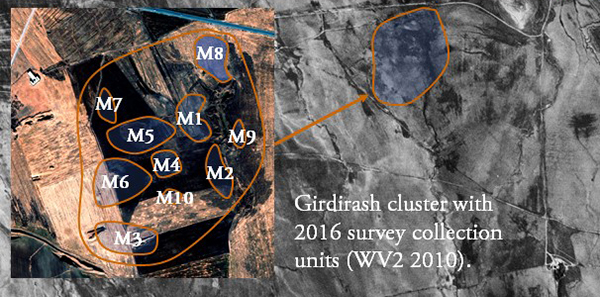

At NN (possible name Girdirash), located to the south of the main Boskin-Chwarqurna road, the project identified a large complex of mounds at the centre of which lies an Islamic period cemetery. Here we undertook a high definition survey and mapping of the site recording 10 separate -but closely related- small mounds (Figure 4). This site offers many opportunities for further research. Once the collected ceramics are fully investigated we will be able to confidently date the occupational history of this large site. Our preliminary assessment of the ceramic evidence suggests that at least 4 – even possibly up to 9 – entities or mounds in the NN (“Girdirash”) cluster have material dating to the LC period. At this time, other periods identified include Iron Age and Islamic – including the Ottoman period.

Figure 4. NN (possible name Girdirash?) survey collection units in 2016 (WorldView-2 satellite image, 2010)

Gulak proved to be another fascinating site. It consists of a large central mound surrounded by a ‘halo’ of small satellite mounds (Figure 5). Preliminary studies of the ceramic evidence suggest that these sites, as well as the main central mound, date to the Late Chalcolithic, Iron Age and Islamic periods.

Figure 5. Gulak in October 2016 (Photos: Henrik Brahe 2016)

B. Investigations of the site of Gulak and its surroundings

During the fieldwork season we paid particular attention to the site of Gulak around which we undertook intensive landscape studies identifying satellite sites of low small mounds and ancient human activities.

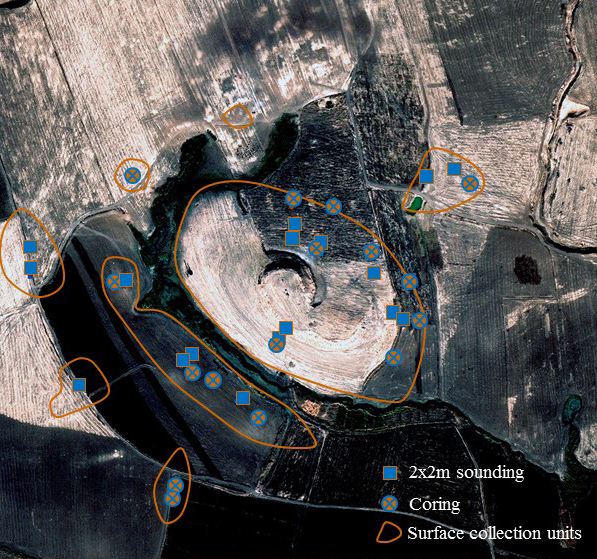

Following a systematic survey of the site, the project carried out a strategy of targeted soundings and corings to investigate the central mound and its surrounding landscape features. This allowed us to explore and plot the full extent of the human topography and to identify the locations of past specialised activities (Figures 6-8).

Figure 6. The location of soundings in the landscape around the site of Gulak (Photo: Tim Skuldbøl 2016)

Figure 7. The excavation of soundings at Gulak (Photos: Henrik Brahe 2016)

Figure 8. Coring in the vicinity of Gulak (Photos: Tim Skuldbøl 2016)

In total, the project excavated 19 small soundings (2x2m): 17 located at Gulak and its surroundings, and 2 soundings at the nearby sites of RPS 56 and 57; and undertook 18 geological corings in Gulak's settlement sprawl (Figure 9). Work resulted in the collection of flotation and soil samples for botanical, C-14 and chemical analyses (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Location of soundings, corings and surface collection units at the Gulak cluster (WorldView-2 image, 2010)

Figure 10. The systematic sampling of flot and soil samples for botanical, C-14 and chemical analyses (Photos: Henrik Brahe 2016).

Soundings not only provided invaluable insights into the nature and sequence of occupation at the sites but, when employed in tandem with coring, allowed the identification of the physical extent of sites through occupational markers such as anthropomorphic soils. This probing beneath the surface has resulted in a more precise reconstruction of the ancient human topography.

Evidence of trash dumping and potential quarry pits were found across the settlement complex of Gulak dating to the Late Chalcolithic period. Results validate proposals previously made by the project regarding the nature of urbanism on the plain. Based on work at Bab-w-Kur and Gulak, we have proposed that the landscape features seen here are a consistent characteristic of early urbanism in this region, i.e. settlement sprawl, trash dumping and potential off-site activity areas representative of an emerging industrialisation and exploitation of the landscape. These new perspectives are challenging assumptions regarding early urbanism per se and suitable methods for its investigation.

C. The study of ceramic evidence and the processing of archaeological samples

During the autumn 2016 season the project continued the analysis of survey pottery, making detailed records (photographs, statistical analyses and drawings). This data will form the basis of the forthcoming publication of the survey itself (Figure 11-12).

Samples (botanical, soil, animal bone, macro-finds and lithic) from the autumn 2016 and previous seasons were processed and prepared for export (Figure 13). These samples will undergo extensive scientific laboratory analyses in Denmark, the USA and France, including C14 dating and soil chemical analyses. This will allow the project to precisely date the collected material and sites, as well as determining the possible functions of the uncovered trash deposit areas and satellites around major sites on the plain.

Figure 11. Ceramic and lithics collected from one of Gulak’s western satellite mounds (Photo: Henrik Brahe 2016).

Figure 12. Cleaning and sorting pottery from soundings.

Figure 13. Flotation work at the expedition house in Boskin (Photo: Henrik Brahe 2016).

Future Plans of the Danish Archaeological Expedition to Iraq

Future research will investigate additional sites on the Rania Plain for signs of urban sprawl dating to the Late Chalcolithic period. Depending of the height of the waters of Lake Dokan, continued excavations at Bab and Kur (which can remain submerged if the reservoir’s water level is too high) are planned for Phase II of the DAEI project beginning in the autumn of 2017.