DAEI investigations in autumn 2015

By Tim Skuldbøl and Carlo Colantoni

Aims of investigations

The fieldwork season on the Rania Plain took place between 1st October and 6th November 2015. Our aims were to continue the excavation of the sites of Bab-w-Kur and survey previously visited sites. Work focused, however, mainly on the investigation and excavation of an extreme large monumental building discovered on the summit of the mound of Bab in autumn 2013.

In the autumn of 2015 the DAEI’s archaeological team consisted of Tim Skuldbøl (archaeologist, Director), Carlo Colantoni (Archaeologist, survey leader), Henrik Brahe (Photographer, artist and UAV/drone specialist), and Alexandra Wood (illustrator and archaeobotanical work).

The team was once more kindly assisted by Barzan Baiz (Museum representative, Sulaimaniyah Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage).

Archaeological investigations

Investigations comprised of:

-

A. Excavation of the site of Bab (the largest mound in the Bab-w-Kur settlement complex).

-

B. Recording archaeological features newly exposed on the surface of Bab by the Dokan Lake’s waters.

-

C. Survey of sites on the Rania Plain undergoing destruction (Figure 1).

A. Excavations at Bab

The twin sites of Bab-w-Kur lie deep within the flood zone of Lake Dokan and are only accessible during a few months of the year. In 2012 fieldwork at the main mound of Bab revealed the remains of a well-planned walled settlement dating to the Late Chalcolithic 2-3 period (4200-3700 BC) at the base of the mound, and widespread pottery kilns and trash pits across its surface.

In the following year the project continued investigations at the neighbouring site of Kur. Surface scraping and excavation exposed a large niched building dating to the Late Chalcolithic 3-4 period (3850-3400 BC) and evidence of systematic trash pitting following its abandonment (see the 2013 Report for details).

In addition, a new set of survey reference points covering both Bab and Kur was established. These allow us to precisely tie architectural plans, topographic maps, off-site activity areas and recorded on-site features – such as the newly exposed ancient trash pits across the surface of the mound of Bab – into a ‘complex-wide’ Bab-w-Kur site grid.

The ‘palace of the lizard king’

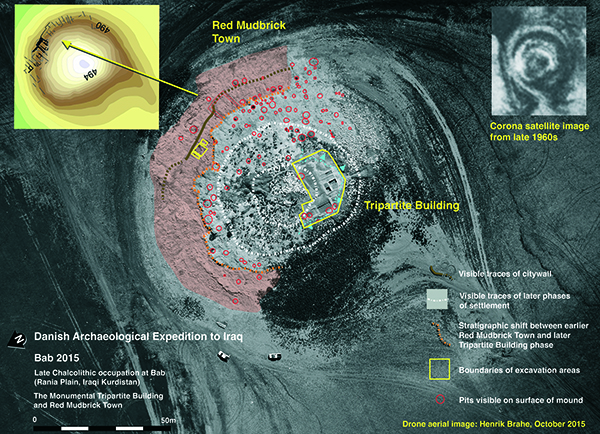

Excavations at Bab were resumed in the autumn of 2015. This work consisted of a clearance and scraping operation (much of the summit of the mound was covered in loose limestone blocks from a now destroyed structure, vegetation and general detritus deposited by the lake’s waters), followed by targeted excavations (Figure 2).

The investigations uncovered a huge tripartite building complex possibly dating to the Late Chalcolithic 4-5 period (3700-3100 BC) (Figure. 3).

The building has a cruciform and symmetrical layout, and consists of a large central room with corridors and a series of flanking rooms. At over 20 metres in width - we still have to establish the full dimensions of the complex - the tripartite building is a substantial structure suggesting a public function (Figure 4). The central room covers the entire width of the building and would have been an imposing reception room.

Preserved in places to over a metre in height, the walls are thick (ca. 60-80 cm on average) and well-constructed (Figure 5). Both the parallel doorways at the western end of the central room are niched. Two large rectangular hearths were found in the central room of this complex. These and the food preparation tools found in subsidiary rooms adjacent to the central room may point towards a formal use for this complex – perhaps as a palace or residence for a local ruler.

It is unusually large and well-laid out for the period, and potentially holds great significance for understanding the changes society was undergoing at this time. The name we have given to the building was inspired by the unusual motif of a lizard on a clay sealing found on the surface of the site in 2013.

Contemporary large multi-room and formal complexes are not well known from Upper Mesopotamia, but examples have been found at Habuba Kabira South in Syria, Arslantepe in Turkey and Tepe Gawra in Iraq. Interestingly, the ground plan for the famous “Eye Temple” at Tell Brak in Syria bears striking similarities to the layout of the building at Bab. Further excavation will shed light on the potential similarities between the large complex at Bab and the elite or public structures found elsewhere in Mesopotamia in this period.

B) Recording of archaeological features newly exposed on the surface of Bab

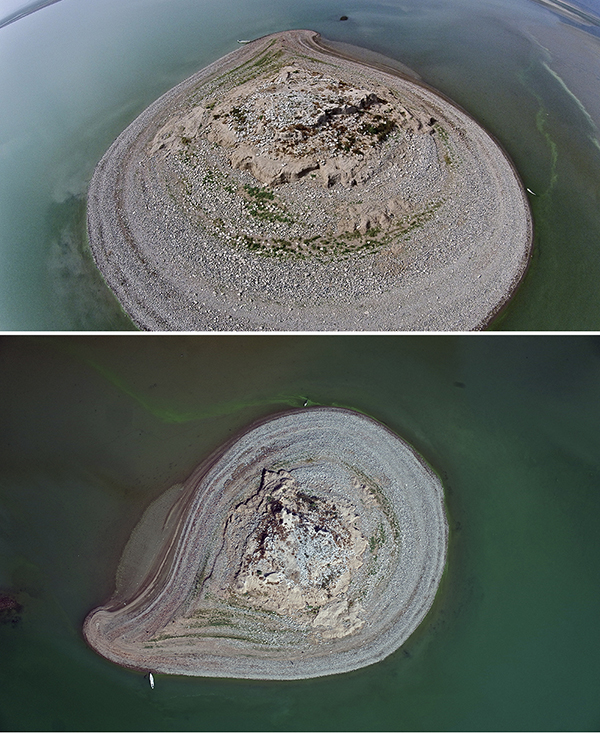

Supplementing the excavation of the tripartite building was the detailed recording of archaeological remains and features – such as walls, trash pits, ovens and storage vessels – newly exposed on the mound’s surface by erosion from the lake’s waters.

As the lake’s waters had only recently receded the surface of the mound was still ‘freshly’ eroded allowing the team to distinguish many archaeological features.

Erosional damage was recorded by the use of on-the-ground photography and aerial drone photography. Not only does this method chart the annual damage to the mound, it allows the project to target for future investigation areas of the mound that are being rapidly lost.

The use of aerial photography also allowed the project to plot these newly exposed features, greatly increasing our understanding of activities undertaken at the site and the various phases of occupation. Perhaps the most interesting finds are the abundant trash pits densely distributed across the upper part of the mound. These suggest large-scale production and disposal activities, and will be the subject of further in-depth investigation. Pits sampled in the 2012 and 2015 seasons have produced ceramics dating the Late Chalcolithic 4-5 period (Figure 6).

The project also recovered a series of exposed large storage vessels possibly dating to the Late Chalcolithic 3-4 period that had been organised in a linear fashion in antiquity, but were now being washed away by water erosion (Figure 7).

During the autumn 2015 season we also processed a large tranche of botanical data collected from the 2013 and 2015 excavations. This task was undertaken by Alexandra Wood at the excavation house in the town of Boskin.

Preservation

At the end of the season (November) the project back-filled the excavated rooms of the tripartite building to protect it from the winter rains and spring floods. Plastic sheeting was placed in each room and then filled with soil.

Media outreach

Finally, we were fortunate enough to have a visit by 7 Kurdish television stations who reported on our activities at the site. The DAEI is always very pleased when we can share our work with the local community and wider Kurdish region of Iraq (Figure 8). These reports can be viewed on the project’s Facebook website: www.facebook.com/babwkur

C. Survey of sites on the Rania Plain undergoing destruction

In the autumn of 2015 the water level of Lake Dokan was very low. This made it possible to revisit and survey several archaeological sites on the Rania Plain that are general difficult to get to and which are in severe danger of being destroyed by the lake’s waters. The sites investigated were Bab-w-Kur-South, Basmusian, and Warankah lower. We recorded destruction of archaeological features with UAV/drone and ground photography. Surface finds were collected systematically from Bab-w-Kur-South and Basmusian. The site of Bab-w-Kur-South was identified and recorded by DAEI in autumn 2012 (see 2012 Report) and surveyed by the NINO team in autumn of 2014 (Figure 9-10).

Basmusian was revisited once more in the autumn of 2015. The citadel area of the site is today in a very bad state of preservation (Figure 11).

Future plans

Research in the autumn 2016 season will investigate nearby sites for occupational histories and follow up signs of early urban sprawl dating to the Late Chalcolithic period. Continued excavations at Bab and Kur are planned for Phase II of the DAEI project scheduled to commence in 2017.